The skies over the South China Sea were unusually quiet that morning, the kind of deceptive calm that precedes a storm. Somewhere below, fishing trawlers bobbed in the waves, their crews oblivious to the sleek, angular shadow slicing through the clouds above. It wasn’t a conventional fighter jet, nor was it a helicopter. It was something else entirely—a machine that seemed to defy the laws of aerodynamics, its rotors tilting with a mechanical grace that spoke of years of secretive engineering. This was China’s first crewed tiltrotor aircraft, a bold declaration of Beijing’s intent to reshape the battlefield of the 21st century.

In a world where military power is measured not just by numbers but by innovation, the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) had just played its latest card. The tiltrotor, a hybrid marvel combining the vertical agility of a helicopter with the speed and range of a fixed-wing aircraft, was no mere prototype. It was a statement. As the aircraft banked sharply over a remote testing range, its matte-gray fuselage glinting faintly in the dawn light, it carried with it the weight of China’s ambitions—and the unease of its rivals.

A Game-Changer Takes Flight

The unveiling of China’s crewed tiltrotor aircraft, reported by The War Zone in August 2025, marks a pivotal moment in global military aviation. Unlike traditional helicopters, which sacrifice speed for maneuverability, or fixed-wing jets, which demand long runways, the tiltrotor offers a rare synthesis of both. Its rotors, mounted on nacelles that pivot from vertical to horizontal, allow it to take off and land like a chopper while cruising at speeds rivaling turboprop aircraft. For a nation like China, with its sprawling geography and contested maritime borders, this capability is nothing short of revolutionary.

The aircraft’s design is shrouded in secrecy, but grainy images circulating on platforms like X reveal a sleek, angular airframe with stealth characteristics. Its low-observable profile, likely incorporating radar-absorbing materials and a minimized infrared signature, suggests a platform built not just for versatility but for survivability in contested airspace. The PLAAF, under the watchful eye of President Xi Jinping, has clearly prioritized a machine that can operate where others cannot—be it the rugged highlands of Tibet, the artificial islands of the South China Sea, or the dense urban sprawl of a future conflict zone.

The Strategic Calculus

To understand the significance of this tiltrotor, one must step back and view it through the lens of China’s broader military strategy. Beijing’s defense doctrine has long emphasized “active defense,” a concept that blends preemptive strikes with rapid, flexible responses to emerging threats. The tiltrotor fits this paradigm like a glove. Capable of deploying special forces, conducting reconnaissance, or delivering precision strikes from austere forward bases, it gives the PLAAF a tool to project power in ways previously unimaginable.

Imagine a scenario: a crisis erupts in the Taiwan Strait. As U.S. carrier strike groups maneuver in the Pacific, Chinese tiltrotors launch from hidden airstrips on the mainland or reclaimed reefs. Carrying elite operatives or advanced sensor suites, they infiltrate contested zones, gathering intelligence or neutralizing key targets before vanishing into the night. Their ability to loiter, hover, or sprint at over 300 knots makes them maddeningly difficult to counter. Add in the potential for mid-air refueling—hinted at by unconfirmed reports of a “buddy refueling” capability—and these aircraft could sustain operations far from home, complicating the plans of any adversary.

The tiltrotor’s versatility extends beyond direct combat. In a disaster response, it could deliver aid to remote regions, reinforcing China’s soft power. In a high-intensity conflict, it could serve as a command-and-control node, coordinating swarms of unmanned drones like Kratos’ Clone Ranger. The possibilities are as vast as they are unsettling.

The Technological Edge

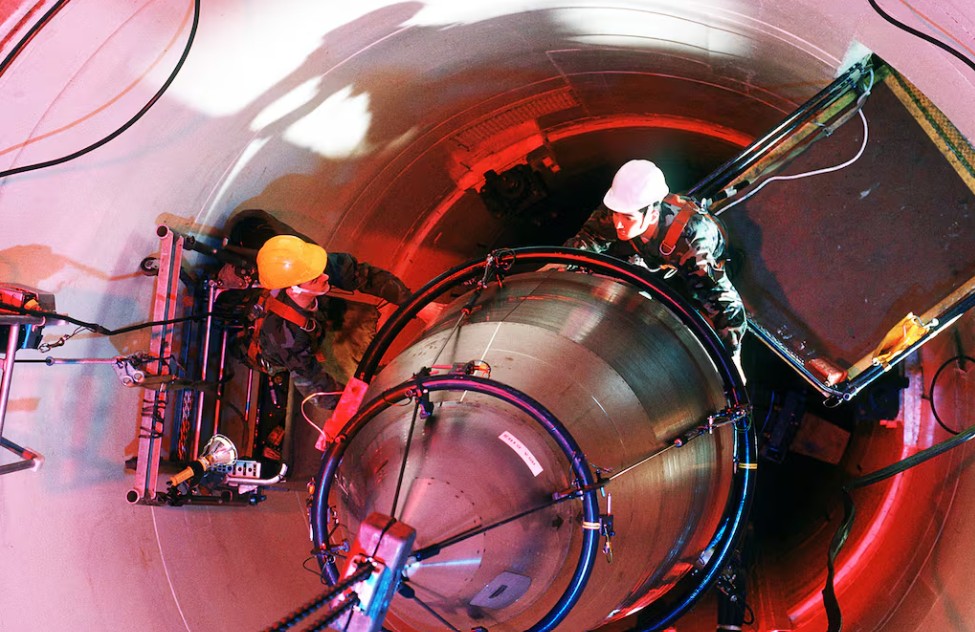

Developing a crewed tiltrotor is no small feat. The United States, with its V-22 Osprey, has decades of experience in this niche field, yet even the Osprey has faced challenges—cost overruns, mechanical complexities, and a steep learning curve. China’s entry into this arena suggests a level of engineering prowess that Western analysts may have underestimated. The PLAAF’s tiltrotor likely leverages advances in composite materials, fly-by-wire controls, and possibly even artificial intelligence to stabilize its complex flight dynamics.

Speculation on X points to a twin-engine configuration, with each nacelle housing a powerful turboshaft engine optimized for both vertical lift and forward thrust. The airframe’s stealth features—faceted surfaces, concealed engine intakes, and a tailless design—mirror those of China’s J-20 stealth fighter, hinting at a shared design philosophy. If equipped with an electro-optical targeting system or a compact radar, the tiltrotor could engage both air and ground targets with precision, a capability underscored by the J-20’s appearance in Kratos’ own renderings as a notional threat.

Yet the real wildcard is the “buddy refueling” capability. If true, this would allow one tiltrotor to refuel another in mid-air, extending its range and endurance. Such a feature would reduce China’s reliance on vulnerable tanker fleets, a critical factor in a Pacific theater where airfields and refueling assets are prime targets. The U.S. Air Force’s exploration of similar concepts for its Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) program suggests that this idea is gaining traction globally, but China’s implementation could give it a decisive edge.

The Global Implications

The debut of China’s tiltrotor sends ripples across the geopolitical landscape. For the United States, it’s a wake-up call. The Pentagon’s CCA program, with designs like General Atomics’ YFQ-42A and Anduril’s YFQ-44A, is still in its infancy, focused on unmanned systems. China’s crewed tiltrotor, by contrast, blends human decision-making with cutting-edge technology, offering a flexibility that drones alone cannot match. The U.S. Marine Corps and Navy, both exploring CCA concepts, will need to reassess their timelines and priorities.

For regional powers like Japan, South Korea, and Australia, the tiltrotor is a stark reminder of China’s growing reach. Its ability to operate from short, improvised runways—potentially even small ships—could alter the balance of power in the Indo-Pacific. India, with its own border tensions with China, will likely view this development with alarm, particularly given the tiltrotor’s potential to deploy forces rapidly in mountainous terrain.

NATO allies, too, must take note. While China’s tiltrotor is tailored for the Pacific, its technology could be exported or adapted for other theaters. A Russian variant, built with Chinese assistance, is not unthinkable, nor is a commercial derivative for global markets. The proliferation of such technology could reshape alliances and arms races alike.

The Shadow of Saber Warrior

Curiously, the tiltrotor’s design echoes a forgotten concept from the 1990s: Lockheed Martin’s Saber Warrior. That uncrewed drone, with its pickle-fork configuration and stealthy profile, was a visionary but unrealized project. The resemblance to China’s tiltrotor raises questions about technological lineage. Did Beijing acquire or reverse-engineer Western designs? Or is this convergence a case of parallel innovation? The truth may lie buried in classified archives, but the parallels are striking.

Kratos’ own Clone Ranger, with its similar dual-fuselage layout and buddy refueling capability, suggests that this configuration is no accident. The aerospace industry, it seems, is converging on a design that maximizes internal space, stealth, and operational flexibility. China’s tiltrotor, however, takes this concept to a new level by adding a human crew, a decision that amplifies its tactical utility while introducing new risks.

The Road Ahead

As the tiltrotor undergoes testing, the world watches with bated breath. Will it live up to its promise, or will it stumble like early iterations of the V-22? The PLAAF’s track record suggests a methodical approach, with years of iterative development behind closed doors. By the time this aircraft enters service, it could be a polished, battle-ready system.

For now, the tiltrotor remains a shadowy figure on the global stage, its full capabilities known only to a select few in Beijing. But its implications are clear. In a world where air superiority is no longer guaranteed, China’s tiltrotor is a bold gambit—a machine that could tilt the scales of power in its favor.

As the sun sets over the South China Sea, the tiltrotor climbs into the twilight, its rotors humming a song of ambition and defiance. The storm is coming, and China intends to ride it.