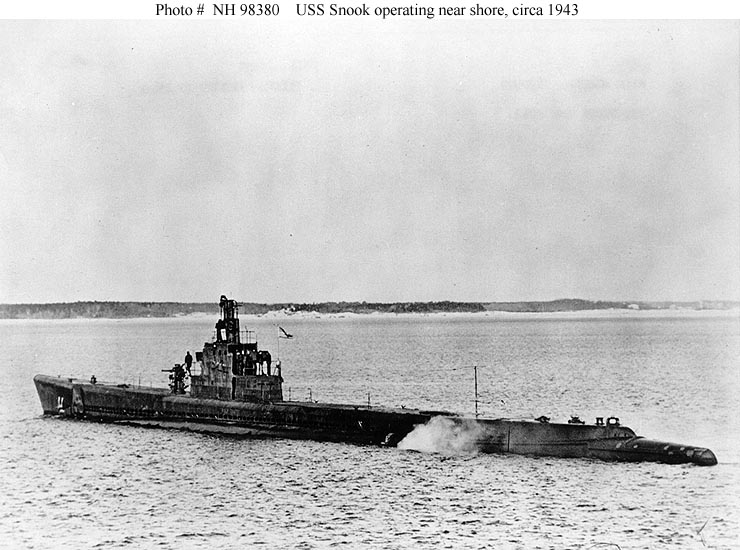

In the cold, unyielding depths of the Pacific, where sunlight dared not linger and the weight of the ocean pressed against steel hulls with unrelenting force, the USS Snook (SS-279) prowled like a specter of war. A Gato-class submarine, she was a marvel of American engineering, 311 feet of silent menace armed with ten torpedo tubes and a crew of eighty souls who lived and breathed the tension of submarine warfare. In the spring of 1945, as World War II roared toward its crescendo, Snook embarked on her ninth war patrol, a mission that would etch her name into the annals of naval legend—and shroud her fate in mystery.

It was March 1945, and the Pacific Theater was a cauldron of chaos. The Japanese Empire, battered but defiant, clung to its strongholds in the Ryukyu Islands, with Okinawa as the linchpin. The U.S. Navy, relentless in its advance, tasked its submarine fleet with choking Japan’s supply lines, a mission that demanded precision, courage, and nerves of tempered steel. USS Snook, under the command of Lieutenant Commander George H. Browne, slipped out of Pearl Harbor on March 12, her hull slicing through the dark waters, her crew steeled for the hunt. Browne, a seasoned submariner with a reputation for cool-headedness, knew the stakes. The waters off Japan were a gauntlet of enemy destroyers, patrol boats, and minefields, each a potential harbinger of doom.

Snook’s mission was straightforward but perilous: patrol the Luzon Strait and the waters near the Sakishima Islands, disrupt Japanese shipping, and gather intelligence on enemy movements. The Luzon Strait, a choke point between Taiwan and the Philippines, was a lifeline for Japan’s war machine, funneling oil, raw materials, and reinforcements to the home islands. Snook’s orders were to sever that lifeline, one torpedo at a time. The crew, a tight-knit band of machinists, sonar operators, and torpedomen, worked in a world of dim red lights and the constant hum of machinery. Every creak of the hull, every ping on the sonar, could signal an enemy above—or the end.

On March 20, Snook struck her first blow. A Japanese merchant convoy, lumbering through the strait under the cover of darkness, fell into her crosshairs. Browne, peering through the periscope in the conning tower, called out ranges and bearings with the precision of a surgeon. “Make tubes one and two ready to fire in all respects, including opening the outer doors,” he ordered, his voice steady despite the sweat beading on his brow. The fire control team, fingers dancing over dials and switches, locked in the solution. “Tubes one and two are fired electrically,” came the confirmation. The torpedoes, Mark 14s with their temperamental magnetic exploders, streaked through the water. Seconds later, the sonar operator reported, “Conn, sonar, units from tubes one and two running hot, straight, and normal.” A deafening explosion followed, and a 6,000-ton freighter, laden with aviation fuel, erupted in a fireball that lit the night. Snook dove deep, evading the depth charges that rained down from escorting destroyers, their sonar pings echoing like the tolling of a bell.

Over the next two weeks, Snook hunted with relentless efficiency. She sank a second freighter on March 25, a coastal steamer on March 28, and damaged a heavily armed transport on April 1. Each attack was a ballet of stealth and violence, the submarine slipping beneath the waves to avoid the inevitable counterattacks. The crew lived on edge, their world a claustrophobic maze of pipes and gauges, where sleep was a luxury and fear a constant companion. Yet morale held firm, buoyed by Browne’s unflappable leadership and the knowledge that every ship they sank brought the war closer to its end.

But the sea is a fickle mistress, and the USS Snook’s luck would not hold forever. On April 8, 1945, she made her last known transmission, reporting her position near the Sakishima Islands. She was coordinating with USS Tigrone (SS-419) for a joint patrol, a standard tactic to maximize coverage and confuse enemy antisubmarine forces. The message was brief, encoded in the clipped jargon of naval communications, but it carried the weight of routine confidence. Snook was operational, her crew sharp, her torpedoes ready. Then, silence.

What happened next remains one of the great mysteries of the Pacific War. Snook was scheduled to rendezvous with Tigrone on April 20, but she never appeared. No distress signal, no debris, no survivors. The Navy, stretched thin by the demands of the Okinawa campaign, could only speculate. Had she fallen victim to a Japanese destroyer’s depth charges? Struck a mine in the treacherous waters of the East China Sea? Suffered a catastrophic mechanical failure? The crew of eighty-two, including Browne, vanished without a trace, leaving behind only questions and grief.

USS Snook (SS-279)

Theories abound, each more haunting than the last. Japanese records, examined after the war, suggest a possible encounter with the destroyer IJN Isokaze on April 9, near the coordinates of Snook’s last transmission. Isokaze reported depth-charging a suspected submarine, but no confirmation of a kill was logged. Another theory points to the dense minefields laid by Japanese forces to protect their southern approaches—silent killers that could have claimed Snook without warning. Some even speculate that a torpedo malfunction, a known issue with the Mark 14, could have turned the hunter into the hunted, a circular run sending a torpedo back to its own ship. But the truth lies buried in the deep, guarded by the ocean’s eternal silence.

The USS Snook’s legacy endures, a testament to the courage of the Silent Service. During her nine war patrols, she sank at least thirteen enemy vessels, totaling over 60,000 tons, and damaged several more. She earned seven battle stars and a Presidential Unit Citation, her crew’s valor etched in the Navy’s records. Yet it is the mystery of her loss that lingers, a reminder of the price paid by those who fought beneath the waves. In the words of a submariner’s prayer, they remain “on eternal patrol,” their sacrifice a beacon for those who follow.

The Pacific, vast and unforgiving, keeps its secrets well. Somewhere beneath its surface, the USS Snook rests, her hull a silent monument to a crew that faced the abyss and did not flinch. For those who read this, remember their names—not just Browne, but every sailor who manned the diving planes, loaded the torpedoes, and listened to the sonar’s haunting song. They were the shadow warriors, the ones who struck from the deep, and their story, like the sea itself, is eternal.